To say it with roses… or not…? That is the question

Valentine’s Day is imminent and that always leads to a debate within the floristry world about whether or not to give roses as a symbol of someone’s love.

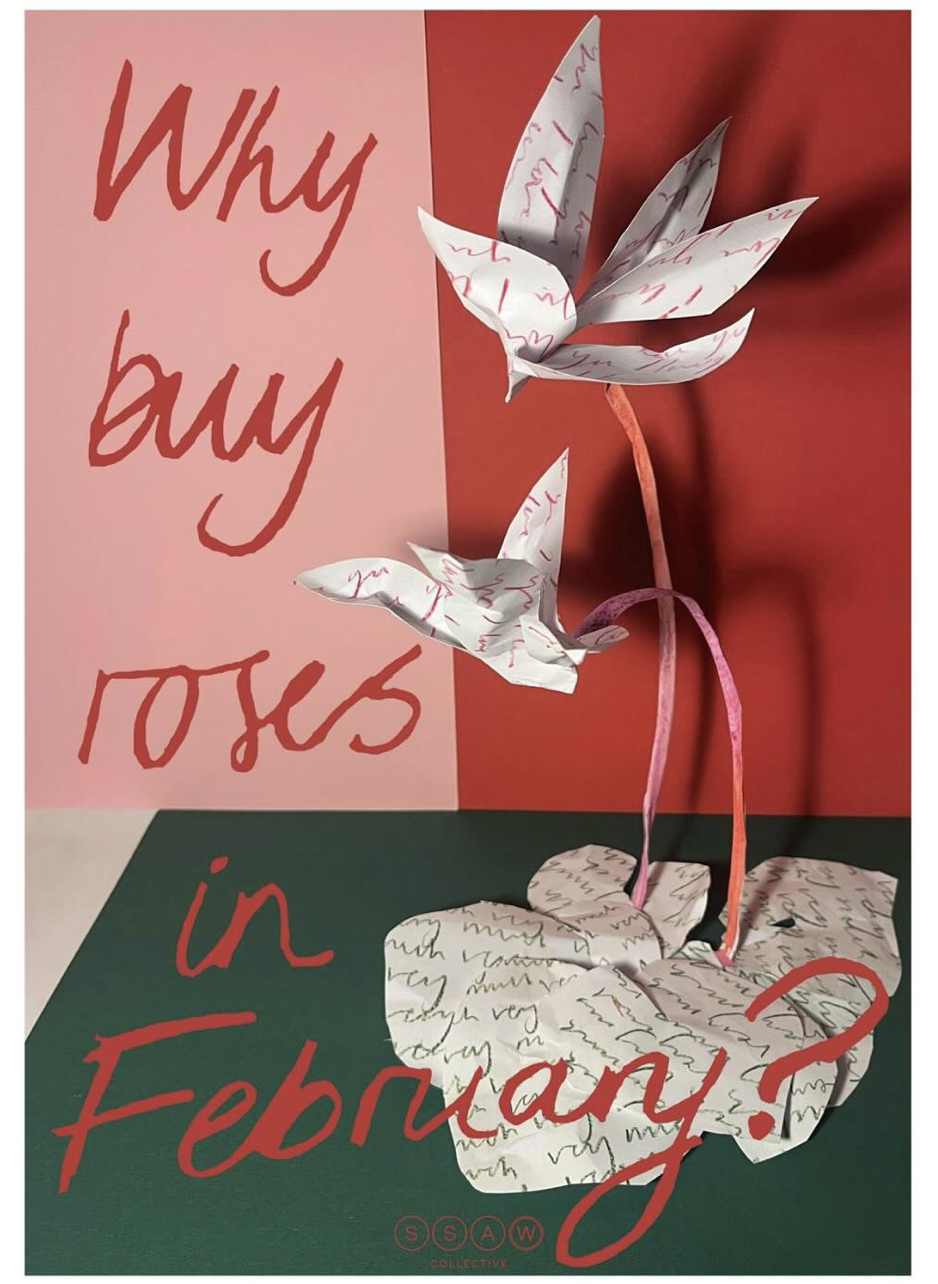

SSAW Campaign Poster designed by @rosalindfreyaclaire

Roses have symbolised love in many cultures for hundreds of years, but the sending and gifting of roses for Valentine’s Day is a more recent development with the introduction of a globalised supply chain which enabled florists to source roses in February, as they don’t grow in the UK at this time of year.

It is estimated that around 220 million roses are sold in the UK for Valentine’s Day every year. I have talked before about the sustainability concerns surrounding industrial scale flower growing, so I won’t go into the environmental and social issues again here, but I encourage you to read my earlier journal entry if you haven’t…

Instead, I want to talk about the debate. And I want to talk about choice. And most sexily of all, I want to talk about transparency… or the lack thereof.

The Roses in February debate

The SSAW Why Buy Roses in February? campaign has been running since 2021. Their objective with the campaign is simply to get more people in the UK to ask that question: “Why buy roses in February? Criticising is not the answer, carbon off setting is not the answer but conversation might just find us a solution.”

This year’s campaign included an article by Linz Kinchin from The White Horse Flower Company. In it, Linz writes “Why buy roses in February? Because they lift our spirits, bringing joy; a perennial favourite regardless of the season, roses are the nation’s most beloved and iconic bloom.” … ”Imported flowers, like tea and coffee, form part of our culture, enveloping us in the familiar, given in love and received with appreciation.” … and “Because not to would be commercial suicide.”

I thought Linz’s article was brilliantly written. It was a brave thing to do given that voicing an ‘opposing view’ into what might be deemed an echo chamber can be a scary thing to do. But what I thought was so great about it was that it was thought provoking and it opened the conversation. Indeed, I’ve been thinking about it ever since, and now I’m writing this…

As is so often the case with these complex issues, there are many shades of grey that are all too often distilled into black and white in the world of social media. It isn’t as simple as ‘if you buy roses, you’re an environmental destroyer’ and ‘if you don’t, you’re an anti-capitalist eco-warrior.’

It comes down to choice

As Linz points out, imported products, like tea and coffee - and flowers - form part of our culture. And if someone wants to say I love you with roses, then that should be their choice, and they shouldn’t be shamed for that. Neither should the person who sold them.

It all comes down to individual choice.

Personally, I wouldn’t choose to buy roses to tell someone I love them in February. I love the way flowers connect me to nature, to the natural landscape as it is at any moment in time, and (environmental and social questions aside) imported roses just don’t do that for me. I appreciate the scarcity of flowers right now which means that when they come I enjoy them even more. So I choose to wait until the ‘not Pat Austin’ (an unidentified David Austin rose in my garden) flowers with her insanely heady peach scent in June. (Plus, my contrarian nature rails against me having to tell my husband I love him on February 14th because a commercialised date tells me I have to… I do love you by the way, if you are reading this…)

Again, however, this is my conscious choice. I don’t impose that on anyone else.

BUT, there are two important points to make around choice:

Awareness, knowledge and understanding is important

In order to make a considered choice, you need to understand the choice and the issues surrounding it. Awareness among individual customers about the social and environmental impact of buying roses (or other flowers grown at an industrial scale) is low.

While understanding around provenance, organic farming and seasonality has largely become mainstream for the food industry (the price point question aside), this just isn’t the case for the flower industry. In the main, people don’t seem to think about where their flowers come from or how they’re grown. Why this is the case is a question for another journal entry… but it means that campaigns like SSAW’s and also Natoora’s Radicchio not Roses are really important in helping people learn about these issues.

What they do with that learning is their choice.

Transparency - or the lack there of - makes it almost impossible to make a conscious choice

As Linz points out in her article, roses (and other flowers) “are fundamental to the local economies of those countries, providing employment, boosting welfare and education for a great many communities.” Supporting livelihoods and economic development in overseas markets is an important consideration for many florists and customers.

But (back to the shades of grey) not all roses are grown in the same way. There are some great cut flower growers out there, like Tambuzi Roses. But they are more of an exception than the rule. A recent BBC report into the rose industry in Kenya found employment standards to be harsh. There is also growing concern about the health impacts of high levels of pesticide usage on the farmers.

Obviously not all cut flower growers are ‘bad’. There are a million shades of grey. There are some great companies out there, looking after their employees, paying them fairly and making great strides in their environmental measures to address concerns. And there are those that aren’t. The problem is, there is such a lack of transparency in the international supply chains that it is near impossible for any individual or florist to know who grew their roses and how. And, as a result, it is near impossible for them to make a conscious choice.

I remember the massive impact that the Nike sweatshop scandal of the 1990s had on Nike’s share price and on the fashion industry as a whole. Yet the cut flower sector feels as opaque—and laden with corporate risk—as the fashion sector did back then…

Given that technology in this day and age means that as a consumer, I can know exactly which flock of sheep produced the wool to make my jumper, which person bottled my moisturiser, which farmer packed my veg box, how can it be that the cut flower sector can’t provide a similar level of information to florists and customers? Who grew the flowers? Not at the individual farmer level, but at the farm level. How were they grown? What is the chemical usage? What is the water usage? What impact has their operations had on the local economy and local environment? Are their farmers fairly treated?

If we knew the answers to these questions, then consumers could make a more conscious and considered choice over whether or not they wanted to buy roses in February.

So what can we do?

I implore the industry as a whole to increase transparency. And I implore the huge listed companies that operate within these supply chains, including the supermarkets and letterbox deliver companies, to do better when it comes to communicating how they manage these issues in their own supply chains.

Until then, I applaud SSAW, Natoora, Linz Kinchin and others who are actively trying to raise awareness on these issues without trying to shame anyone. And I applaud all the florists out there trying to navigate this tricky time in a way that aligns with their values and their commercial realities.

If you really want to give roses, you can buy them from Tambuzi in Kenya through The Real Flower Company. Or look for the FairTrade symbol. (And we know this doesn’t overcome the environmental issues associated with flower growing at an industrial scale on the other side of the world, but it’s about offering awareness and choice).

If imported roses aren’t your jam, there are lots of other creative flower options out there. Find your local flower farmer on www.flowersfromthefarm.co.uk and gift a flower subscription for when the flowers start again in April, or give a floristry workshop (ahem…), or give pressed flowers or incredible handcrafted paper flowers… Or take ‘a glass half full’ approach to floral design and cut a handful of winter branches or snowdrops from the garden…

All we can do is equip ourselves with as much knowledge as we can, and then make the choice that feels right to us based on our own values system. No judgement here (unless you actively choose wilful ignorance, in which case…)